The FTC Identifies a “Prime” Candidate for Dark Pattern Enforcement: Key Takeaways

Last week, the Federal Trade Commission announced yet another enforcement action, this time against online retail giant Amazon in connection with its Amazon Prime program. Like most FTC actions, this announcement follows a multi-year investigation – in this case, this action has been brewing since at least March 2021. However, unlike most recent FTC actions that end in a settlement and an announcement of changed practices, this case is heading to court in the Western District of Washington and includes additional allegations under the Restore Online Shoppers' Confidence Act ("ROSCA"), 15 U.S.C. §§ 8401-05.

Because the case is being actively litigated, the complaint against Amazon is currently heavily redacted. What we can see however paints a clear picture and serves as a clear warning for any company that offers subscription programs to consumers.

What is a Dark Pattern?

The name “Dark Pattern” is a broad term that gained popularity around 2021 when the FTC led a workshop on the practice. “Dark Patterns” refer to a design or interface choice that is designed to subvert consumer choice or otherwise impair a consumer’s autonomy or decision-making. Two of the most common places we see Dark Patterns are in the realms of privacy, and here, in recurring (or so-called “negative option”) subscription payment programs. One could argue that techniques that push customers towards making a specific choice, such as making a purchase, are the hallmarks of effective marketing; however, Dark Patterns are techniques that cross the line into being unfair.

Although the FTC and others have created a taxonomy of nicknames for specific Dark Patterns – “Forced Action,” “Interface Interference,” “Obstruction,” “Misdirection,” “Sneaking,” “Confirmshaming,” to name just a few mentioned in the Amazon complaint – Dark Patterns still have a bit of a “you know them when you see them” quality to them. This is why it’s helpful to look at past precedent and examples – including the present case – as a guide.

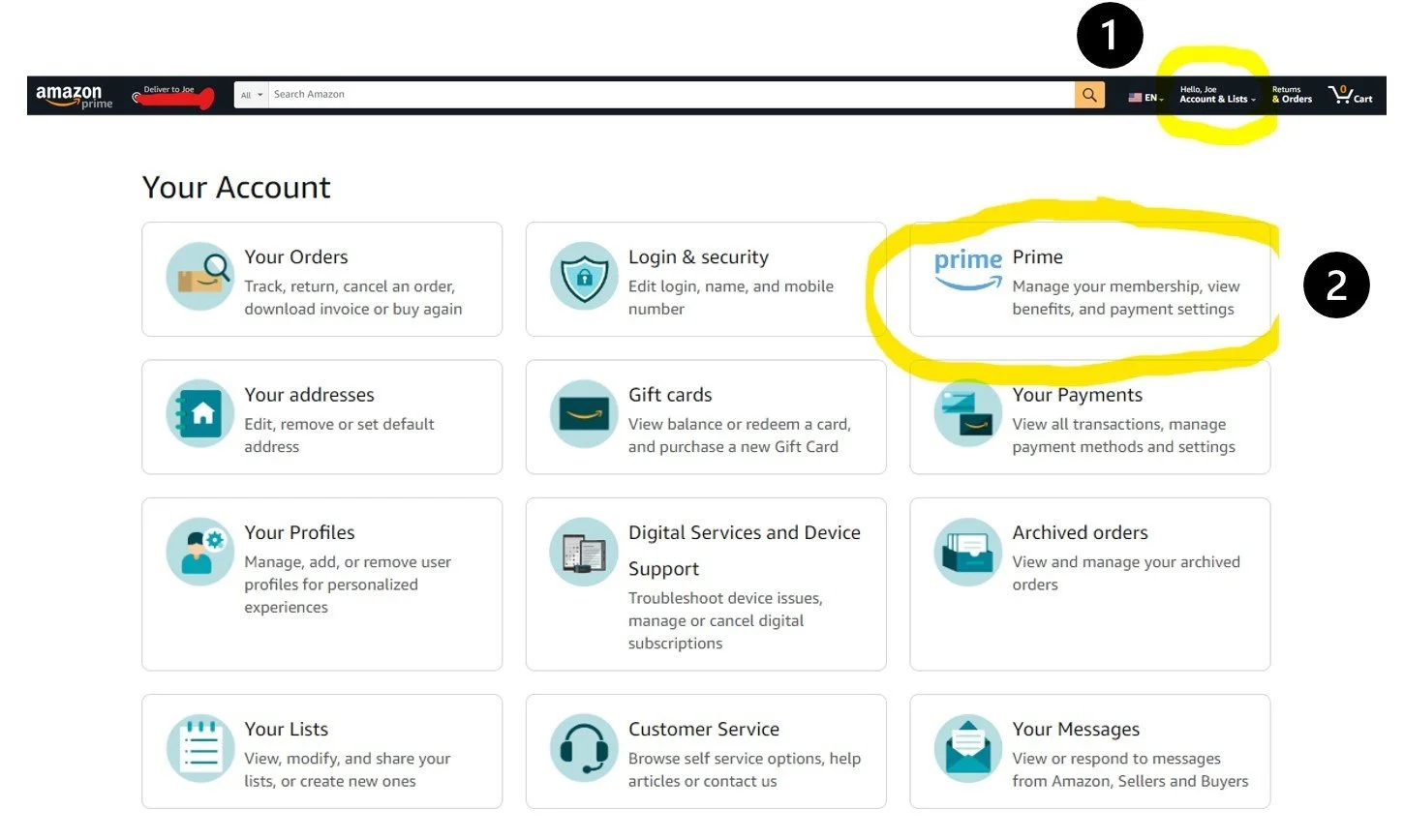

Above: an example sign-up flow cited in the FTC complaint. When the consumer tapped “Get FREE Two-Day Delivery with Prime,” this signed them up for a free trial of Prime, which turned into a full monthly paid subscription unless the consumer cancelled. Below in fine print were the Amazon Prime Terms and Conditions, but that was not enough. Under ROSCA, consumers must give their express, informed consent before getting charged with a recurring transaction. Simply put: browsewrap consent does not count.

What is ROSCA?

Above: an example sign-up flow cited in the FTC complaint. When the consumer tapped “Get FREE Two-Day Delivery with Prime,” this signed them up for a free trial of Prime, which turned into a full monthly paid subscription unless the consumer cancelled. Below in fine print were the Amazon Prime Terms and Conditions, but that was not enough. Under ROSCA, consumers must give their express, informed consent before getting charged with a recurring transaction. Simply put: browsewrap consent does not count.

In the case of recurring subscription payments, the FTC has an even more prescriptive tool at its disposal in the form of ROSCA, 15 U.S.C. §§ 8401-05, which became effective on December 29, 2010. Unlike the FTC’s Section 5 authority which broadly covers any “unfair or deceptive” business practices, ROSCA’s requirements are very explicit. Under ROSCA, an online seller offering a recurring payment feature must, before obtaining the customer’s billing information: (a) clearly disclose all material terms of the transaction, including its recurring nature and how to opt out, (b) get express informed consent to these terms, and (c) offer a simple mechanism to prevent further charges. Here, the FTC has alleged that Amazon failed with respect to all three requirements. (Note that although not explicitly at issue here, California has passed an even stricter law with respect to auto-renewing subscriptions that is even more explicit in the required disclosures, reminder notices, and methods by which a consumer can cancel their subscription.)

Key Takeaways

In addition to taking Amazon to task for failing to adequately cooperate with the investigation, the FTC called out several areas of noncompliance with respect to Amazon’s Prime consumer-facing flows. Rather than go through each violation, we’d like to highlight three key takeaways.

“Passive” (a.k.a. “Browsewrap”) Consent is Never Sufficient for Subscription Sign-ups

When attempting to bind a customer to a contract, companies sometimes require the consumer to make a specific affirmative action, such as checking a box or pressing a button, to manifest their assent to be bound. That type of online agreement is often called a “clickwrap” contract. However, stopping the consumer in their tracks and requiring them to check a box adds friction, so some companies occasionally make use of so-called “browsewrap” contracts, which use a passive disclosure to let the consumer know that by taking some other action (like using the service or confirming a purchase), that constitutes their assent to be bound to the legal terms. Relying on browsewrap contract acceptance is already risky from an enforceability standpoint. In the recurring payments context, it is also an explicit violation of ROSCA.

Takeaway: when presenting a recurring subscription – even one that comes after a free trial – have the key subscription terms included in a separate consent checkbox that the consumer must check before continuing.

2. Design Choices Matter

Repeatedly throughout the complaint, the FTC focuses on Amazon’s design choices as examples of the “misdirection” Dark Pattern. High contrasting colors, visually appealing animations, and designs for every option that the business wants you to pick, changing the design and location of the cancel button from page to page – Amazon used nearly every design trick in the book here.

Above: one of the pages highlighted in the complaint. Despite this page appearing after the consumer has already selected the option to cancel Prime, nearly everything on this page is designed to stall or subvert that decision. A “progress bar” at the top suggests that cancellation is an exhausting, multi-step process; the links in “Your Benefit usage” all lead to pages that would stop the consumer from completing the cancel function. The “Remind me later” has a blue box and marketing text, while “Keep My Membership” has both a big blue box AND an arrow pointing to it. Meanwhile, “Continue to Cancel” is sandwiched in between with no callout.

You don’t necessarily need a degree in UX design to see how this page is drawing too much attention away from key information consumers need to cancel their subscription. And even if it weren’t obvious from looking at the pages themselves, the FTC has alleged that this misdirection was entirely Amazon’s intention. According to the FTC, Amazon not only knew customers were getting confused, but they slowed or rejected changes that would’ve made it easier for consumers to cancel Prime because those changes adversely affected Amazon’s bottom line.

Takeaway: Lawyers need to be involved in approving designs, not just disclosures. And if customers are complaining about either your sign-up flow or cancellation flow being confusing or user-unfriendly, you should act quickly to fix them.

3. Don’t Get into a “Too Many Clicks” Situation

The flow for ending a Prime subscription was allegedly referred to as the “Iliad Flow” in leaked internal Amazon documentation, apparently a nod to Homer’s interminably long epic poem “The Iliad.” Not a good fact for Amazon!

As catalogued in great detail by the FTC, even if a customer was able to initiate the flow, they would be subject to a barrage of large buttons and options, such as an option to switch to annual rather than monthly payments, a reminder about unclaimed prime benefits, an option to “pause” billing rather than outright cancel, and more. According to the complaint, a minimum of six clicks would be required to close an account, across multiple different webpages. On mobile, the process was an eight-page, eight-click minimum process.

According to the complaint, the Iliad Flow was launched in 2016 and altered in April 2023, presumably in response to this investigation. Still, as pointed out by the FTC, even the flow that exists today is overly cumbersome, requiring a minimum of 6 clicks on desktop:

Above: the current Amazon flow, with each click highlighted. As an aside, the “Remind me before renewing” option above Step 4 appears to be off by default, despite Cal. Bus. & Prof. Code § 17602(b)(2) requiring a reminder to be sent at least 15 days and not more than 45 days before the automatic renewal offer or continuous service offer renews.

Takeaway: Count your clicks. The FTC will count each click in both your sign-up flow and your cancellation flow. If your cancellation flow requires too many clicks across too many pages, you need to find ways to streamline.

Conclusion

In just the last 6 months, we’ve covered major FTC actions against Epic, BetterHelp, and Xbox, all related to consumer issues. It’s clear that the FTC is on a roll with enforcement, with little sign of letting up. Now is a great time to examine your company’s subscription flows with a critical eye: Tyz Law counselors Joe Newman, Olivia Clavio, and Jonathan Downing can help.